From Galway to Leenane Perspectives on Landscape , 2013, National Gallery of Ireland , Curated by Anne Hodge,curator of Prints and Drawings.

From Galway to Leenane: Perceptions of Landscape

National Gallery of Ireland

15 June – 29 September 2013

ESSAY by JASON OAKLEY 2013

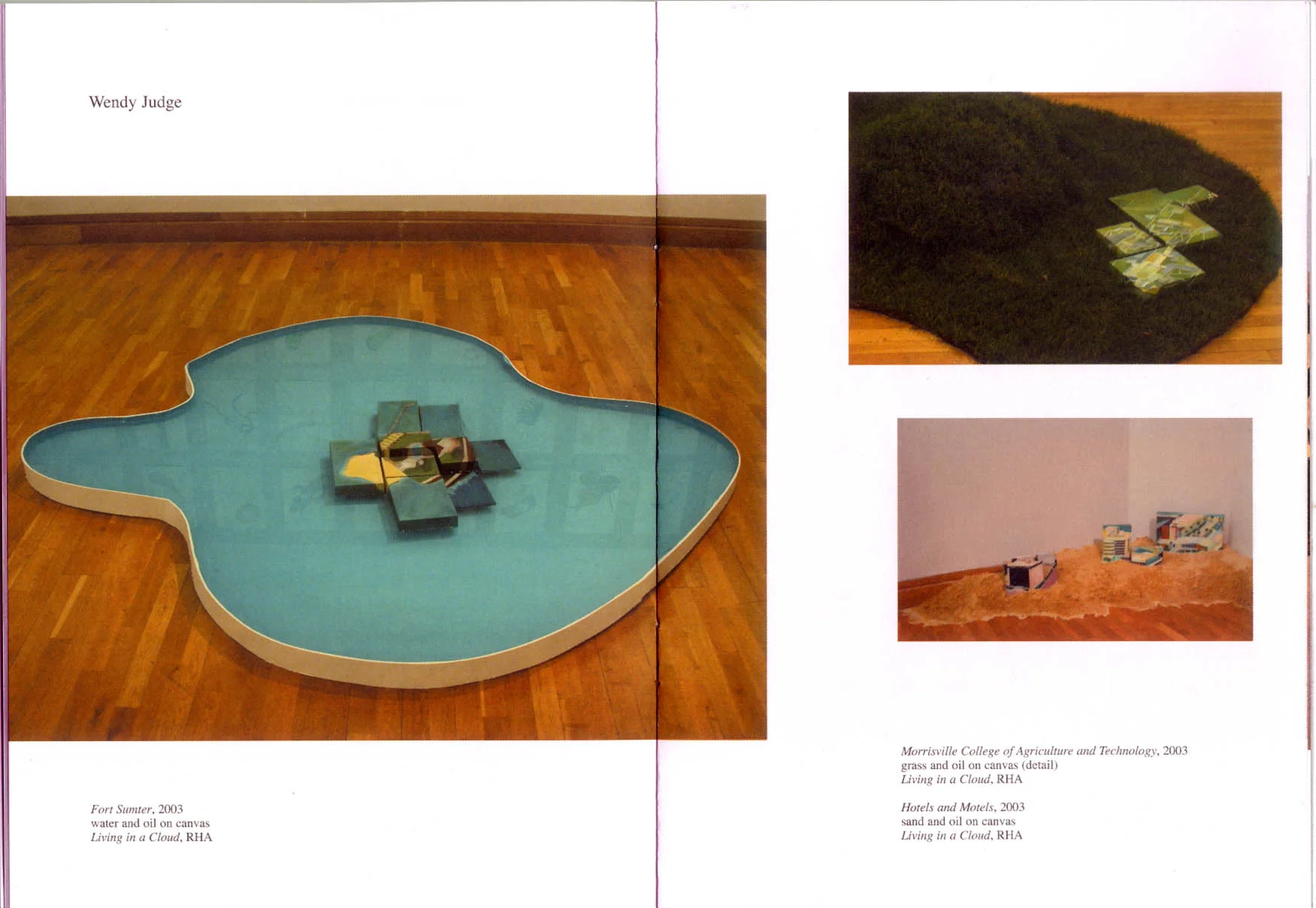

Wendy Judge’s work embodies all the irony, objectivity and self-depreciating humour we expect from contemporary art. So what on earth is it doing in a mausoleum of dead artists work like the National Gallery of Ireland? The answer is that, a selection of Judge’s pieces (b. 1967) play a brilliant part in ‘From Galway to Leenane: Perceptions of Landscape’ (15 June – 29 September), an exhibition showcasing the NGI’s 2008 acquisition of 41 watercolours by William Evans of Eton (1798 – 1877), notable in their near documentary depiction of pre-famine Ireland. Despite the near 200 year gap between them, Evans’s and Judge’s works compliment each other, adding up to an enthralling visual essay on travel, time, geology, modernity and identity.

NGI curator Anne Hodge, invited Wendy Judge to contribute to the show, after seeing the artist’s work at Dublin Contemporary in 2011. Hodge thought that Judge could come up with some creative ways to lift the Evan’s collection out of the stuffy domain of the aficionado of Victoriana; and be up to the challenge of addressing the restrictions that come with working in the climate controlled environment of the Print Room, where Evans aged and fragile works would be displayed.

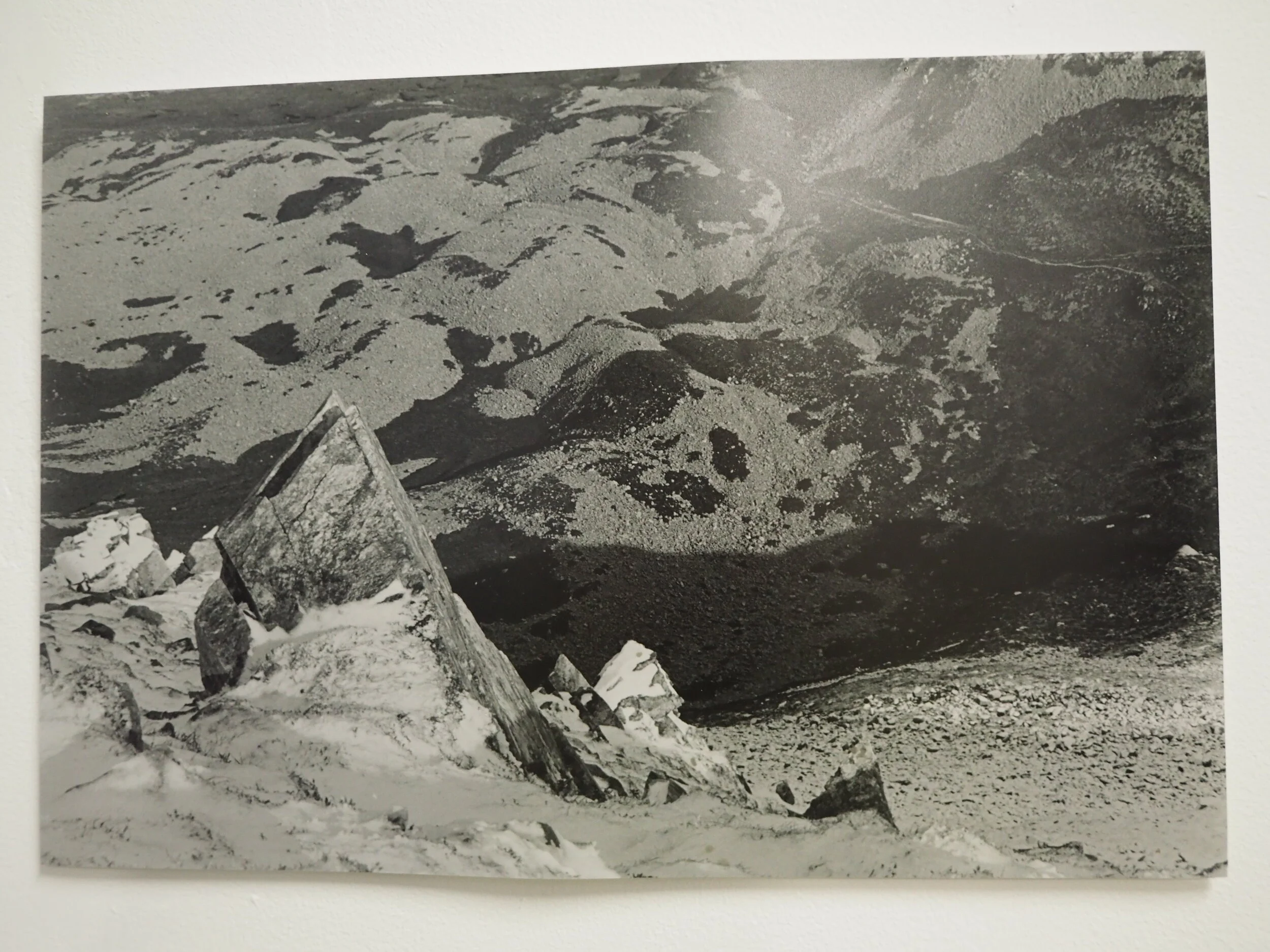

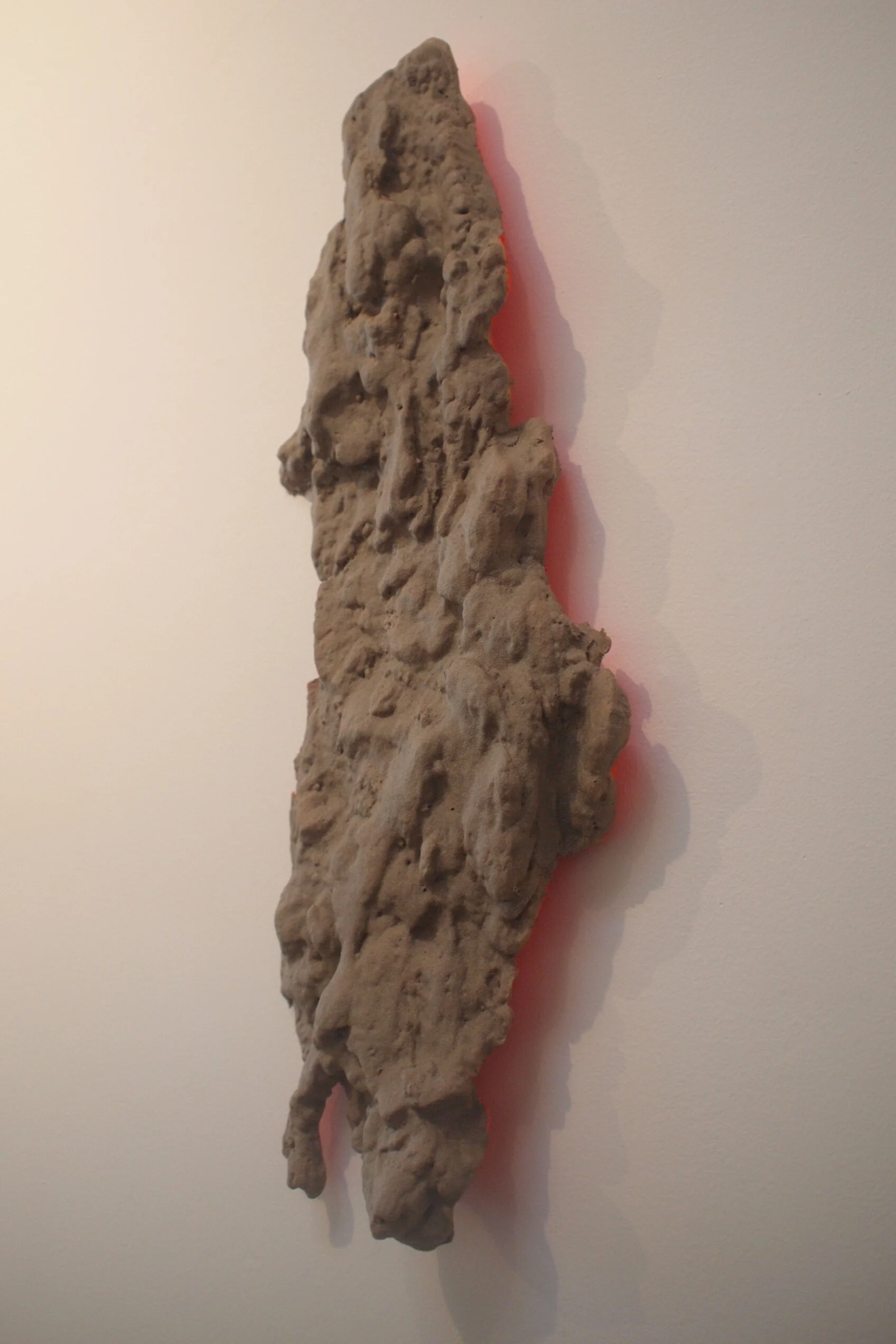

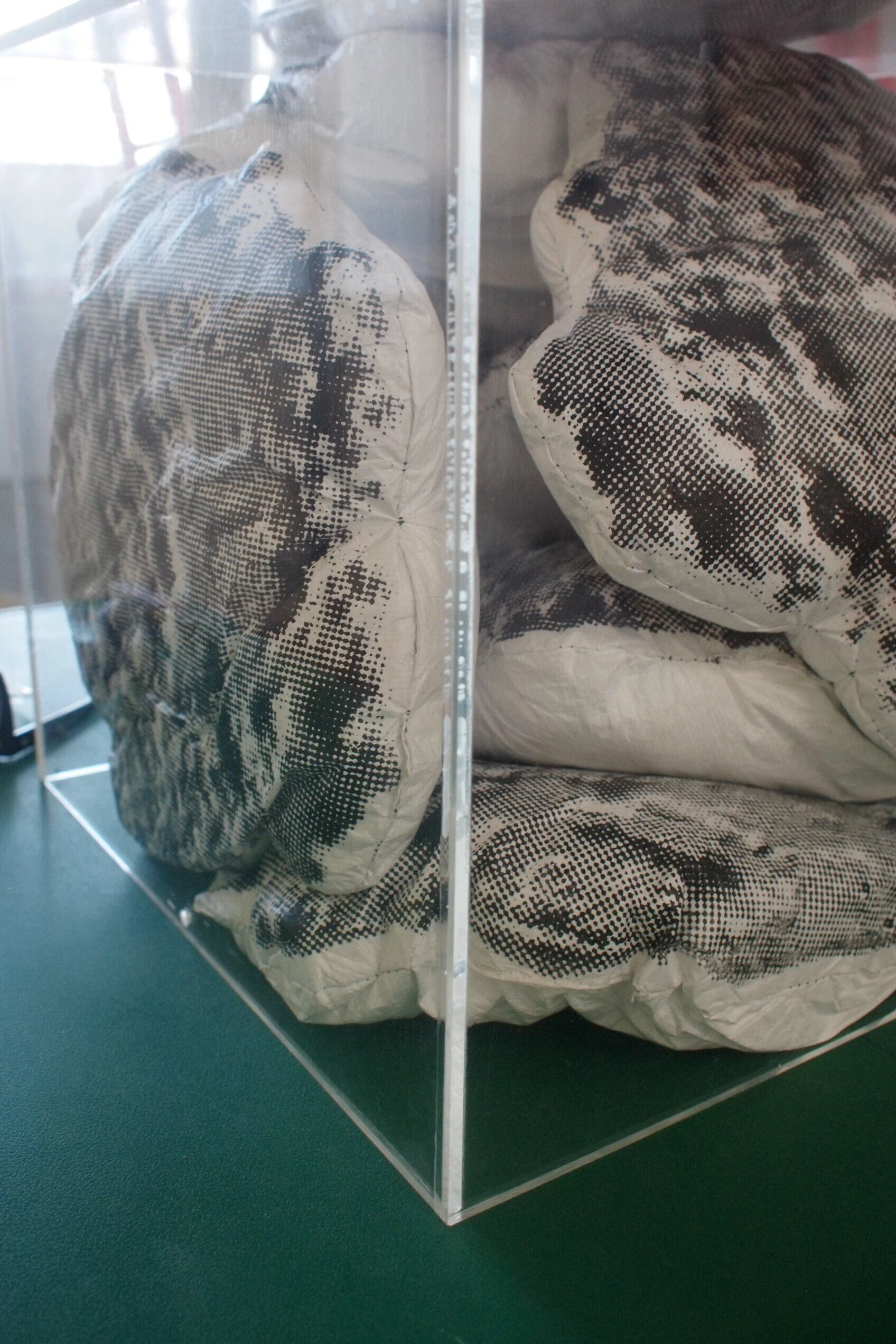

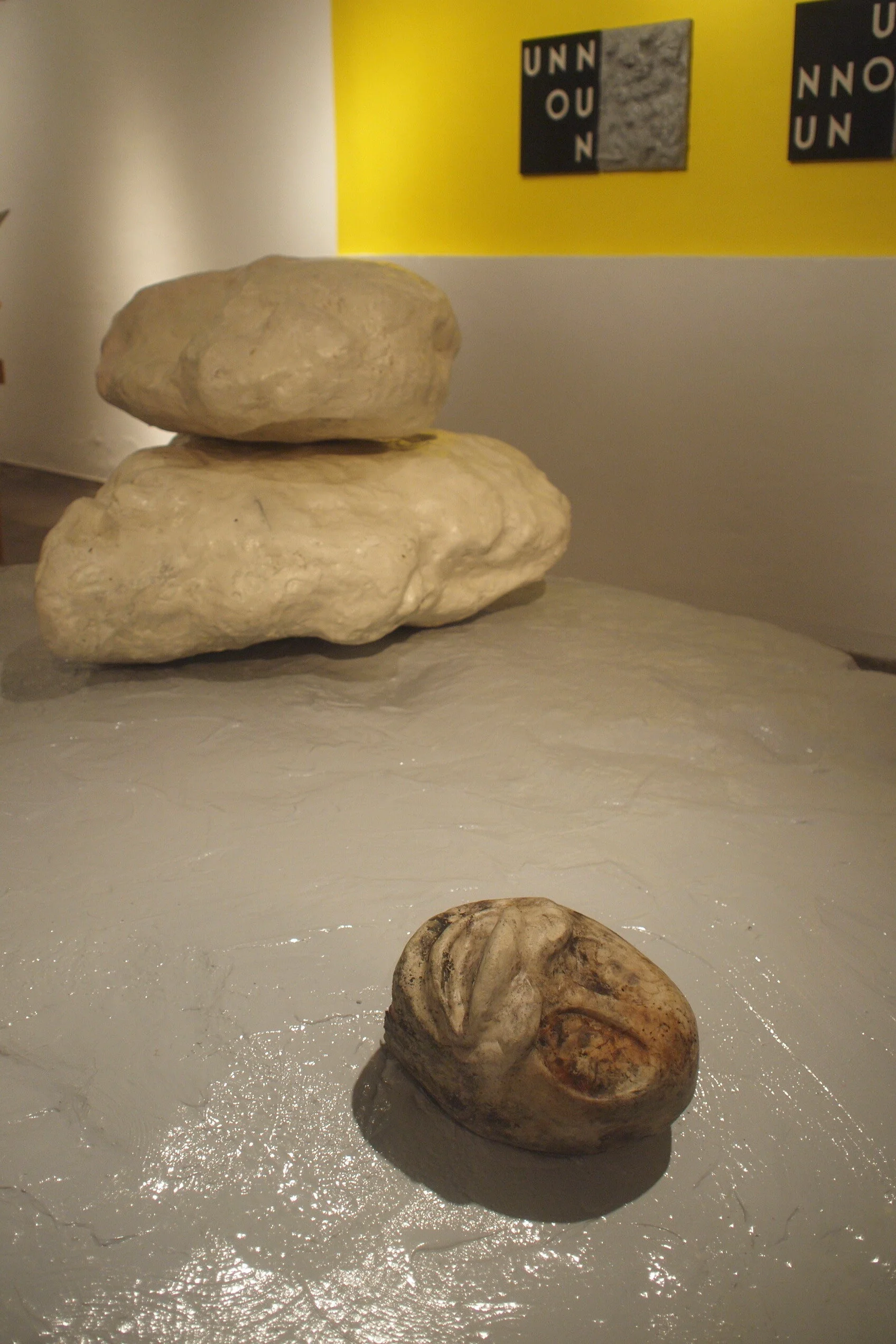

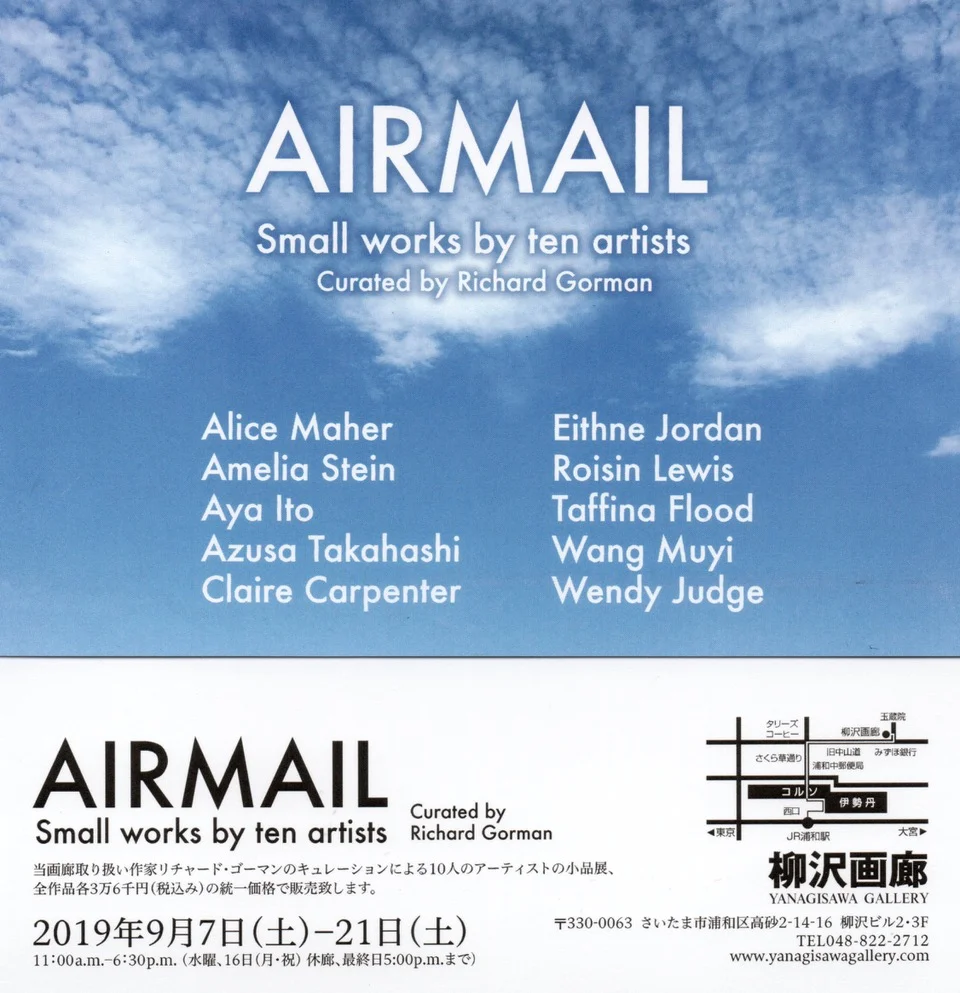

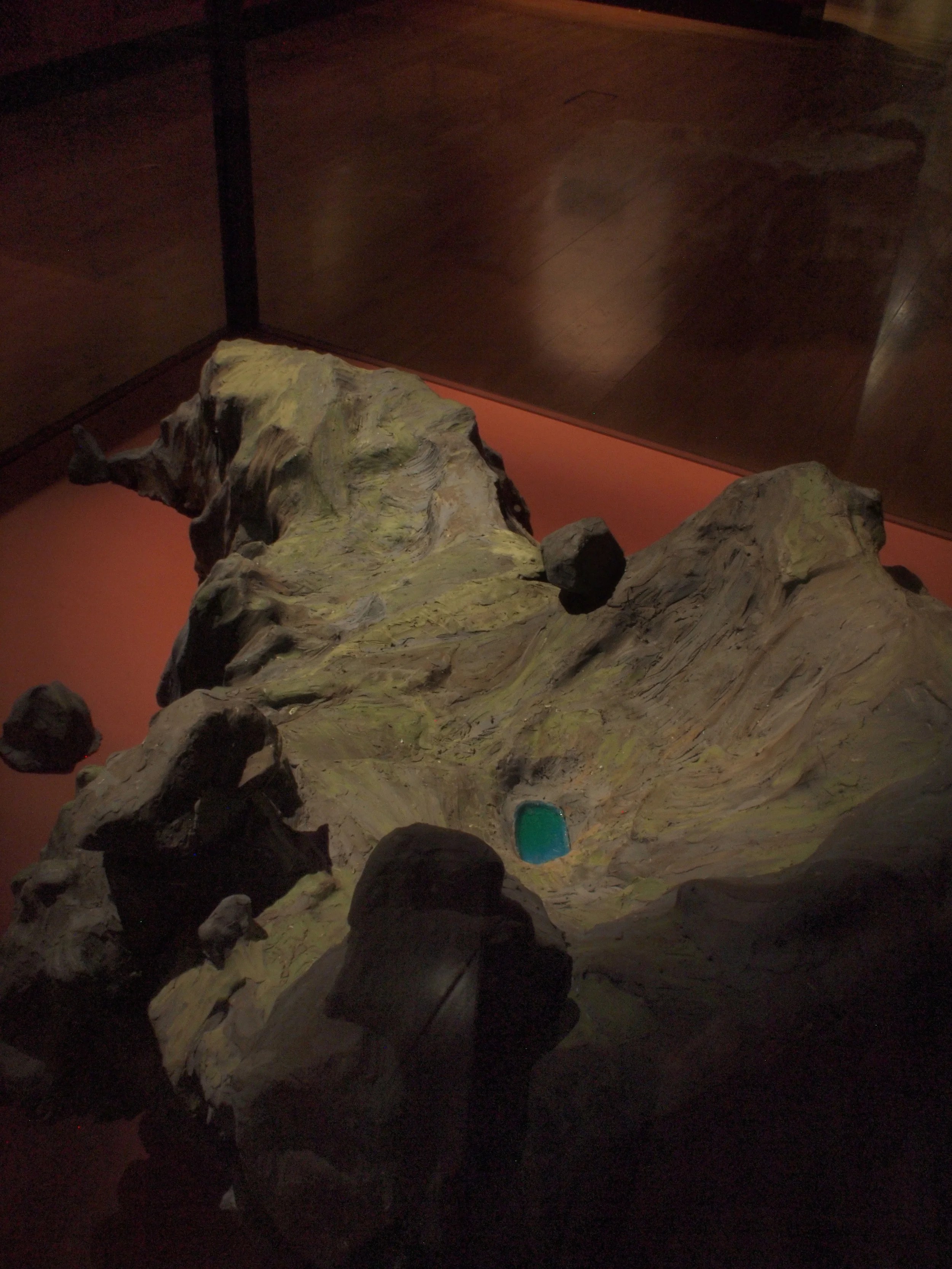

The exhibition’s showstopper is Wendy Judge’s ‘A Grand Precipice’ (2013) a large-scale landscape diorama, fabricated from foam, plasticine and wax; and presented in an imposing wooden framed display cabinet. Integral to the work is a pair of reverse binoculars, which visitors are invited to view the work with – giving it at colossal scale and immense sense of mass. While the work is based on Achill Island, it has an otherworldly presence, resembling the an asteroid or planetoid – albeit one prettily surmounted by a small lough. In a 2012 show at Pallas Projects in Dublin the artist crafted works based on the geographic features of Mars.

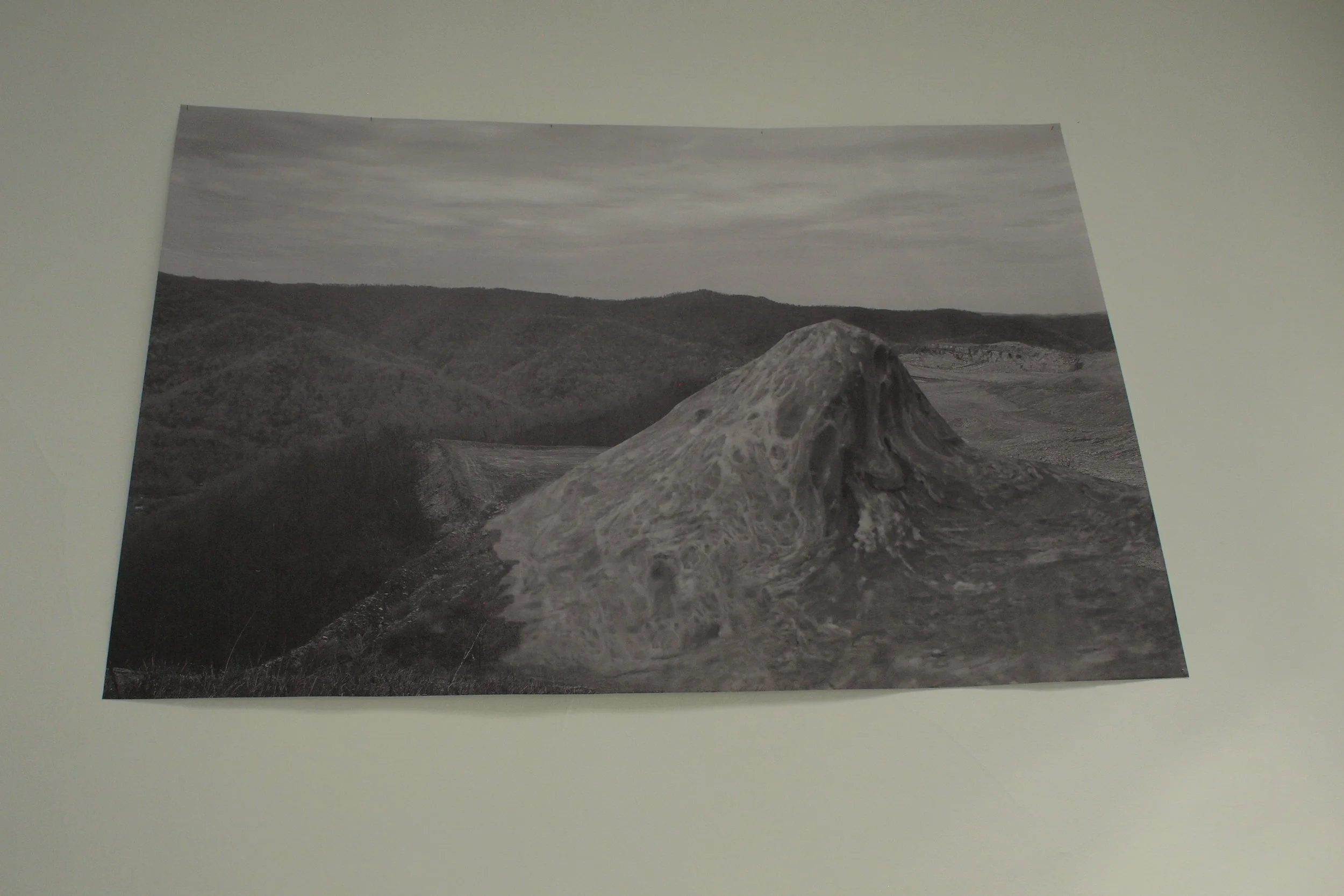

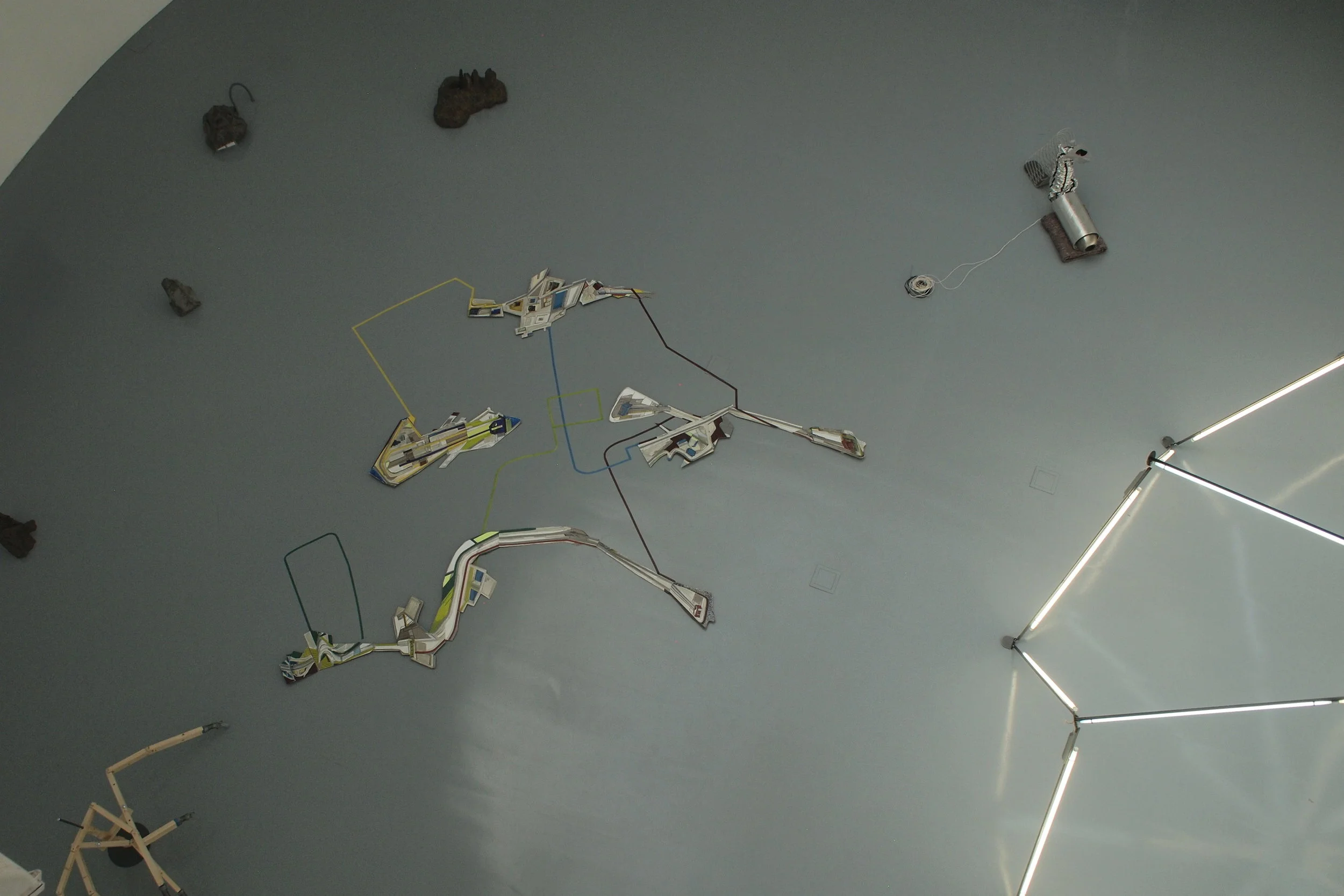

Exploding out of a corner, at ceiling height, is a glossy black cluster of boulder like objects. Asteroids, fungal spores, a molecular structure? This is Judge’s sculpture ‘Mind There Now’ (2013). Viewing this work through the attached reverse binoculars helps you fall into a world either cosmic or microscopic.

Evan’s journeys in Connemara were made possible by technology. The building of the Oughterad to Clifton carriage road, by the engineer Alexander Nimmo (1783 – 1832), had opened up in previous decades the West of Ireland for the first time to tourist travel. In 1851 of the Great Midland Railway made mass travel easier and prompted publishing boom of Irish related travel writing. Evan’s travelled in Galway and Mayo in 1835 and 1838, and the works on show in this exhibition were commissioned as the basis for illustrations for Ireland, Its Scenery and Character, by Mr & Mrs C Hall, which became known as ‘Halls Ireland’, which was republished in 1851. A third – and compelling – element of this exhibition is a display nineteenth century travel memoirs and guides, including background information on the impact of map-making, coach roads and the railway building on the early tourist industry in Ireland.

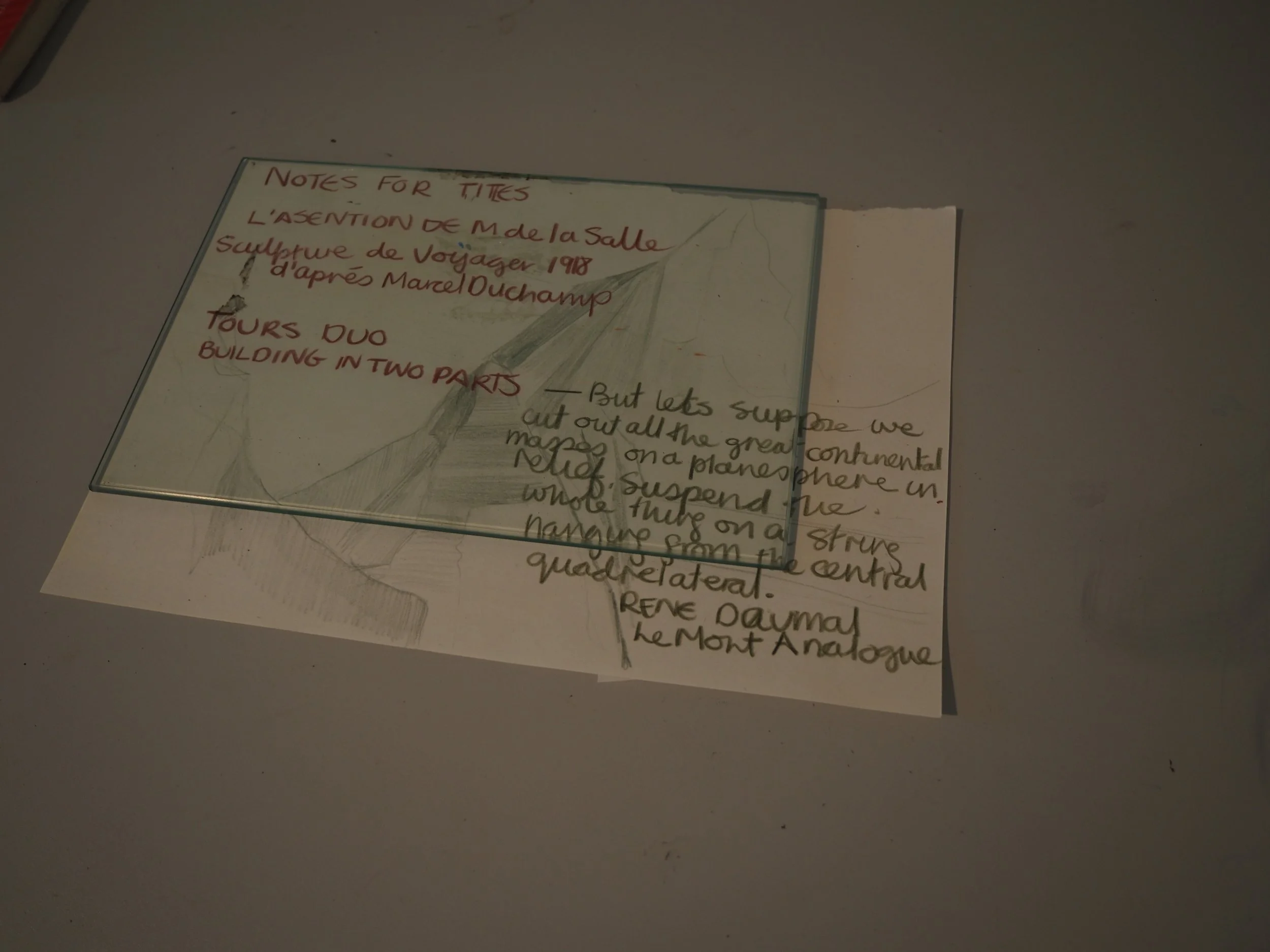

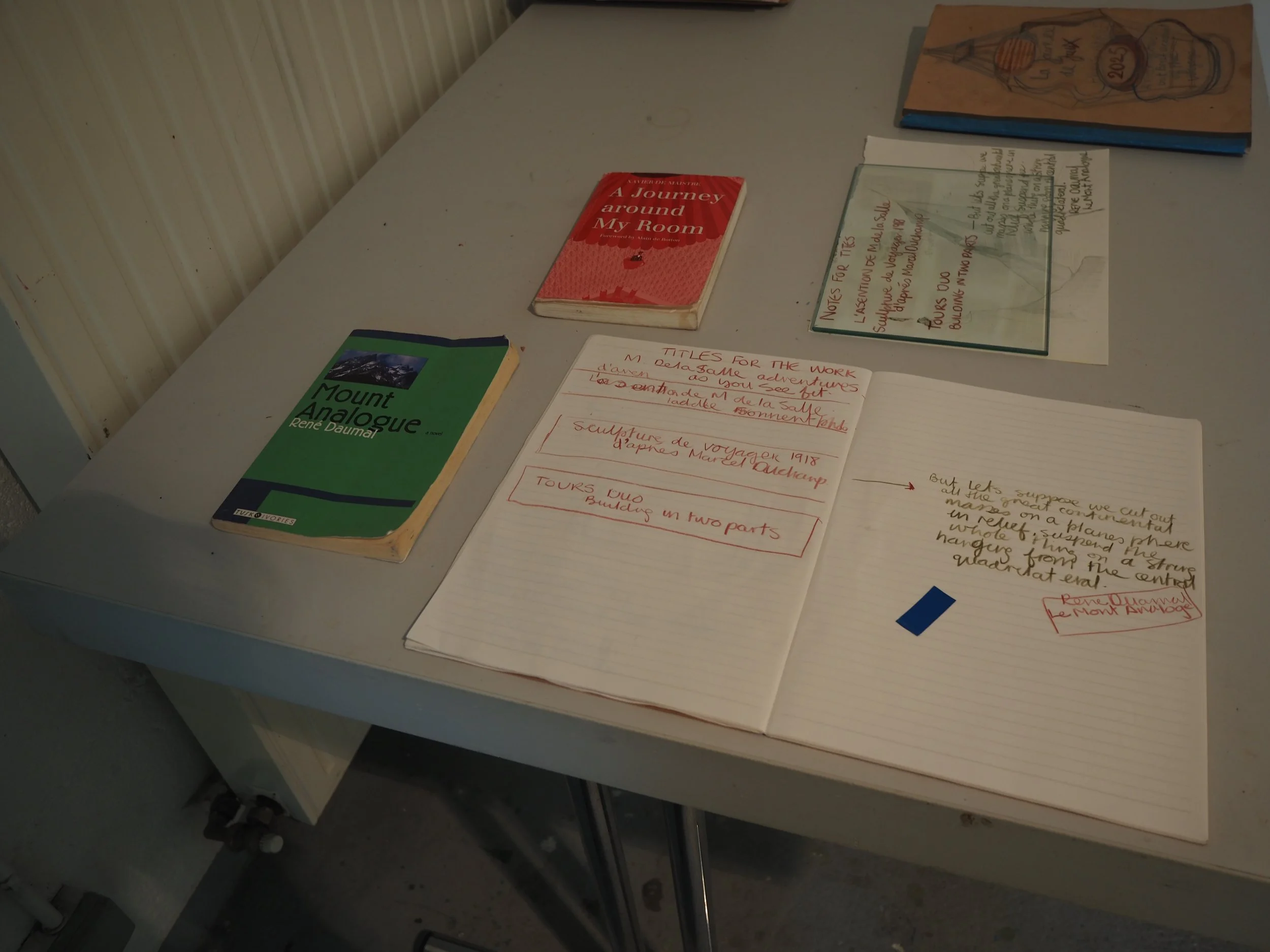

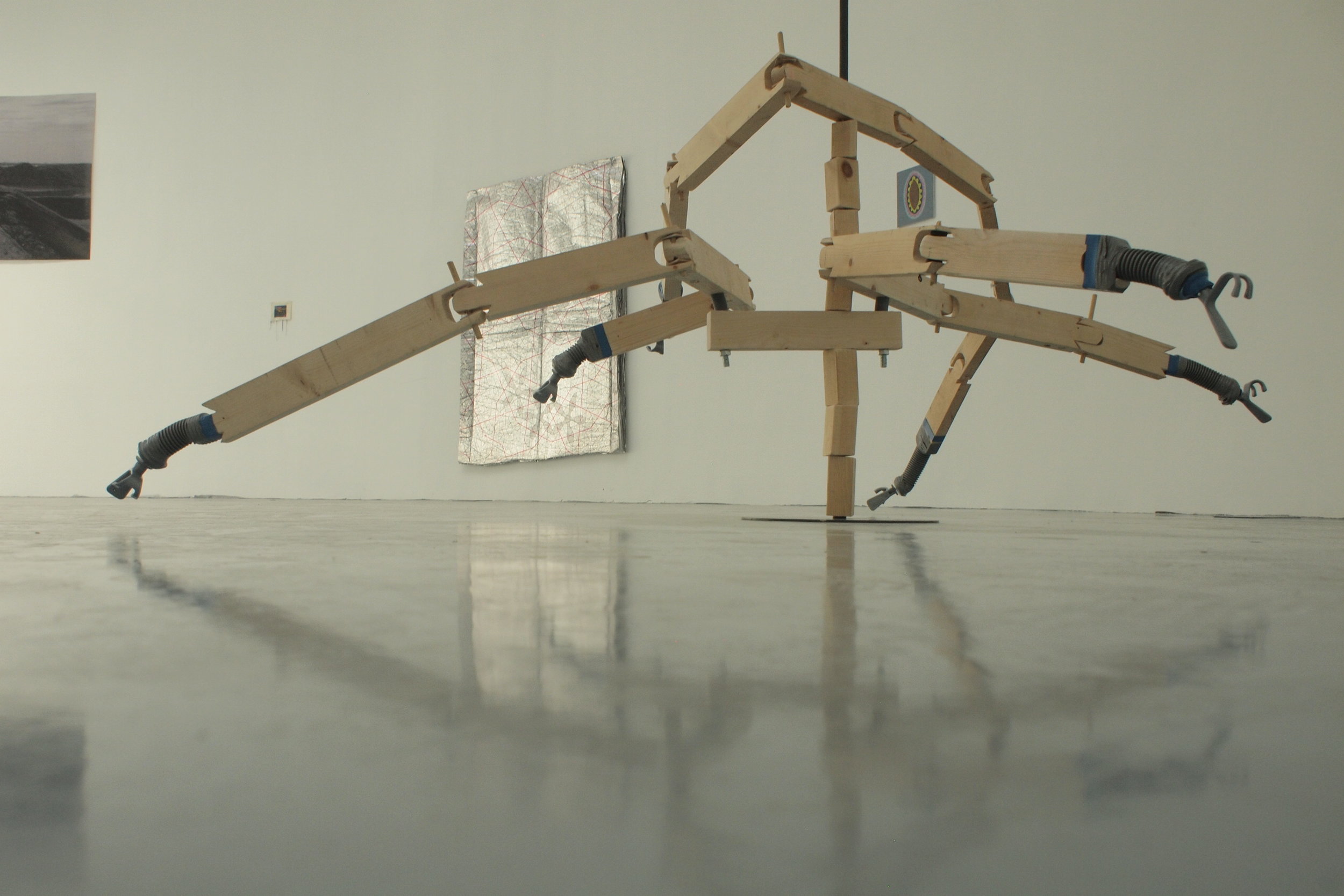

Imagined journeys are at the core of this exhibition. Evan’s work allows us to time-travel, back to pre-famine Connemara and at the same time encounter views that remain cherished and appreciated by contemporary tourists. Judges is an arm-chair traveller, making works derived from the Internet and other secondary sources – including literary ones – and rendering the ‘virtual’ concrete, albeit obliquely, in the form of models and drawings.

The cliché’s of tourism are re-appraised in this show. Isn’t there something fascinating about the quirky prejudices and expectations we all carry to places we visit for pleasure? For a Victorian like Evans, his perspective was coloured by romantic notions of ‘picturesque view’ and the exotic primitiveness Ireland and the Irish. Certainly, amongst Wendy Judge’s baggage is a more resigned view about the ultimate ‘unknowability’ of the world – why bother to attempt first-hand experience of places in the context of the torrent if images and information of our digital age? Nonetheless Judges works communicate a sincere fascination with the wild geologies of the west.

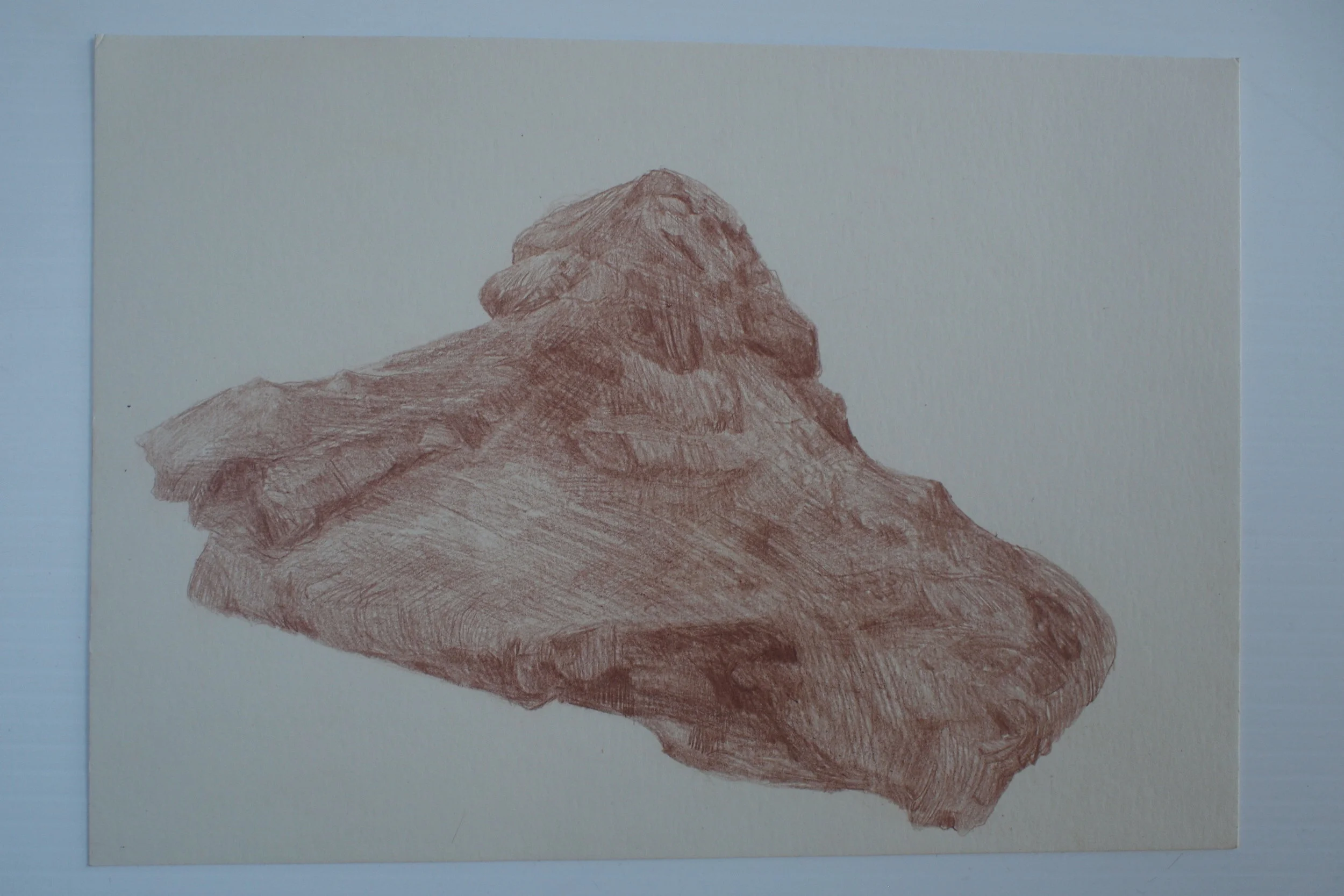

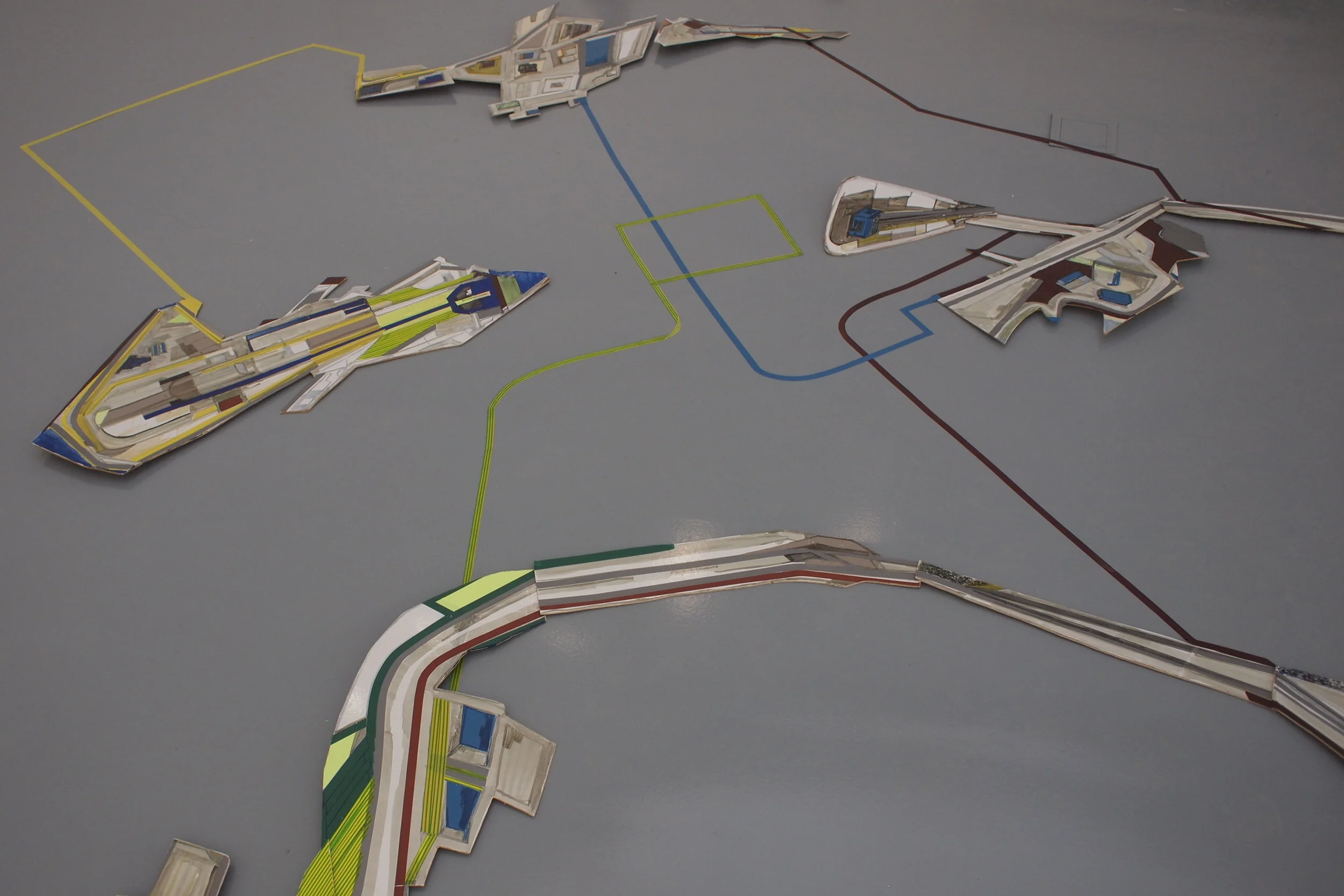

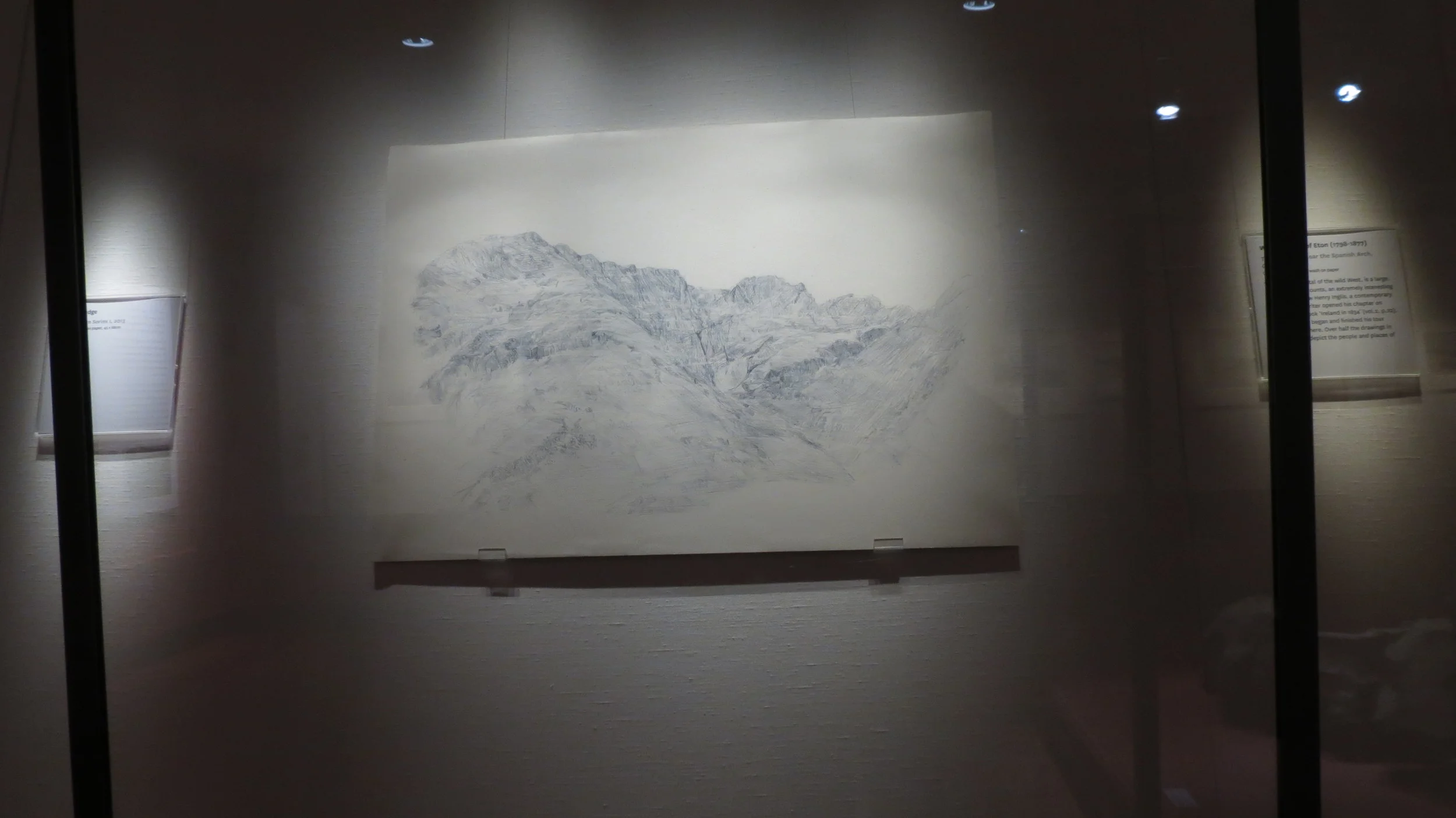

Three drawings by Judge are inserted into the hermitically sealed wall displays of Evan’s works in the print room. Collectively entitled ‘The Western Series I, II, III’, they are drawn in blue coloured pencil, these detailed studies of mountain ranges resemble technical drawings or blue-prints; they are suggestive the layers of data embedded in landscape – cartographical geological, historical, cultural – bringing to mind the profound slowness of geological time versus the rapidity human cultural time.

There is a deep poignancy to Evan’s seemingly innocent patronising touristic views. The Connemara people Evan’s depicts – granted little more than local colour or exotic ‘types’ at times – once had sustainable relationship to their homelands and each other. This was a world tragically eradicated by the famine. There was certainly always poverty; Evan’s even shows it in some his works. But the people we are shown had a vibrant culture, were connected to place, and embodied generation’s worth of knowledge, skills and beliefs – such of the kind on show at the superb Museum of Country Life in Castlebar.

This exhibition wears its profundity lightly. The supporting wall texts and captions blessedly free from the clunky mixed metaphors, fanciful assumptions and assertions and conceptual ‘positions’ that can mar even the support materials for contemporary art exhibitions. Visitors are left free to pick there way through a mix of artworks, objects and information, and play the mental ping-pong with the inter-linked ideas running through Evans and Judge’s works.

‘From Galway to Leenane’ unexpectedly pushes a lot of emotive buttons. For sure, it is a timely ‘holiday show’, albeit one that meshes time and space; and puts landscape art, alongside the contexts of tourism and perceptions of national identity – both cultural and geographic. Musing on foreign and local readings of Ireland is more than on-trend right now, as we look forward to the decade of centenaries of Irish independence, albeit from a mundane quagmire international economic woe, that for the time being is blotting out any celebratory sense of self-determination.

Jason Oakley